Obituaries

May Their Memory Be A Blessing

Our obituaries honor the lives and memories of those who have passed with unique stories, sharing the memories of those who have touched our lives and hearts. On this page, we invite you to read these meaningful tributes, leave personal messages, and connect in honoring lives that have shaped our world.

Lee Aaron Garry

2025

Lee Aaron Garry, the only child of Idelle and Sam Goldberg, has passed away at age 86.

A native Angeleno, Lee graduated from Fairfax High School, UCLA (undergrad) and USC (law school). While he enjoyed engaging in the banter characteristic of that crosstown rivalry, his true loyalty was always to his beloved Bruins.

In 1970, he married Barbara and they enjoyed 55...

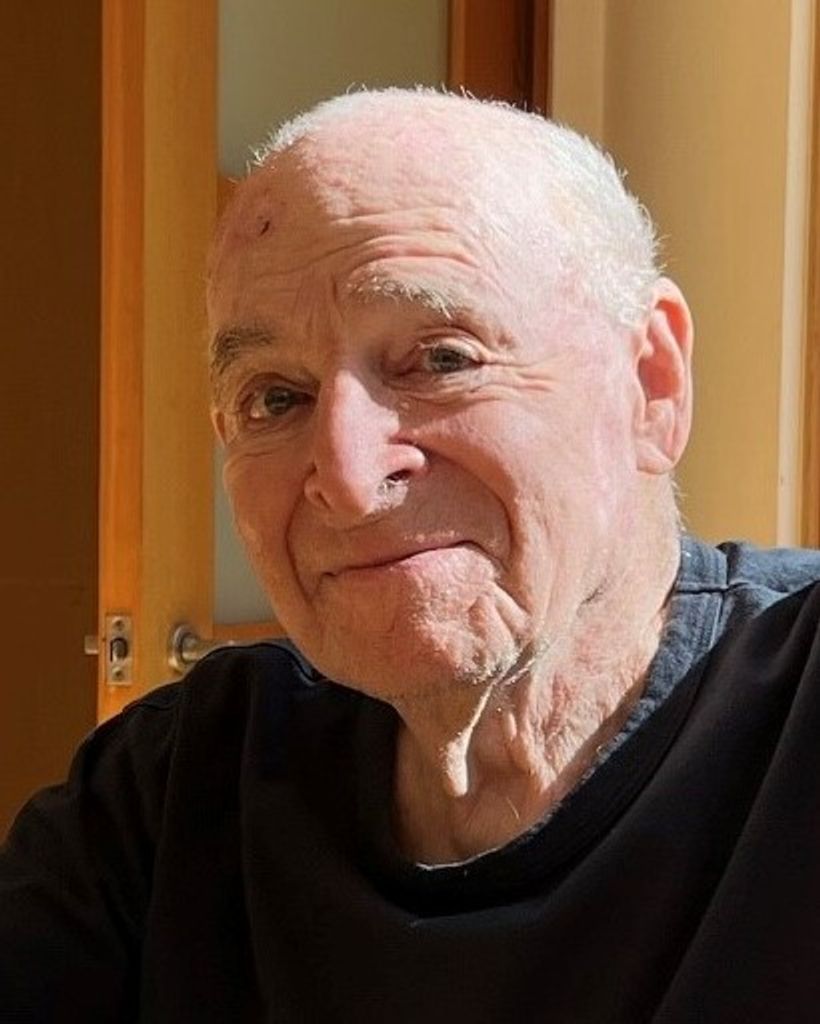

Edward Louis Lux

Jun 13, 2025

Edward Louis Lux (96), of Shaker Heights and Pacific Palisades, CA, passed away peacefully with family close by, on Thursday, June 12th in Santa Monica, CA.

Ed was born in Cleveland on June 2, 1929 to Louis and Doris (nee Littman) Lux, both of Shaker. In the summer of 1954, Ed met Marjorie Baylson and after a few months of long-distance...

Estelle Alper

Jun 11, 2025

We are saddened to announce that longtime KI member Estelle Alper passed away Wednesday, June 11 at the age of 97. She has been a member of KI since 1962.

Born in New York City, Estelle married David Alper in 1950. In 1962, they moved from New Jersey to Pacific Palisades, where Estelle remained until 2024. Estelle and David shared 58...

Lori Stein

Jun 10, 2025

Lori Stein (1938-2025)

Lori Stein was born in Berkeley, CA on July 4th, 1938, to Libby and Nat Frug. Being an only child, Lori spent much of her time around her school friends, Jane and Bill, and her cousins Ron, Jerry, Norma, and Linda. She had several hobbies, including reading, photography, dancing, and writing. But more than anything, she loved to...

Ken Stein

Jun 10, 2025

Ken Stein (1968-2025)

Ken Stein, 56, of Highland, CA, tragically and unexpectedly passed away, along with his mother, Lori Stein, on June 10th, 2025.

He was born in Los Angeles on July 30th, 1968, to Lori and Alan Stein. Shortly after high school, Ken enlisted in the army, worked in the Conservation Corp, and worked at March Air Force Base. Beginning in...

Sherri Morr

Jun 7, 2025

Sherri Morr, aged 80, passed away peacefully in her sleep in Los Angeles on June 7 following a courageous journey with dementia.

Sherri was born on May 13, 1945, in Baltimore, Maryland. She spent most of her childhood years in Norfolk, Virginia and graduated from Granby High School in Norfolk in 1963. A graduate of California State University, Northridge, Sherri earned...

Joni Sue Eliahou

May 29, 2025

Joni Eliahou, 70 of Simi valley California passed away peacefully on May 29th 2025. Joni was born on April 25th, 1955, in Brooklyn, New York to Joseph and Frances Jacobson. She enjoyed spending time with her family. Joni was predeceded in death by her mother Frances, father Joseph, brother Wally, Sister Phyllis, and nephew Howard. She is survived by her...

Ellen King Kravitz

May 24, 2025

KRAVITZ, Ph.D., Ellen King, born May 25, 1929, in Fords, New Jersey, passed away in Beverly Hills, California, May 24, 2025. Her beloved husband, Hilard L. Kravitz, M.D. predeceased her on August 9, 2006. She is survived by daughters Julie and Heather; step-sons, Kent, Kerry and Jay Kravitz, as well as many other close family members. She graduated with a...

Elise Sinay Spilker

May 22, 2025

Days after celebrating her 77th birthday, Elise Sinay Spilker lost her almost seven-year battle with ovarian cancer. Her passage, like her life, was meaningful, full of charm, and touching. She accepted her death with the same grace that defined her life. She was born and raised in Los Angeles to adoring parents Barbara Mott and Joseph Sinay. It is there...

Bertha F. Serkin

May 19, 2025

It is with deep sorrow that we announce the passing of Bertha F. Serkin. Born on December 8, 1922, in Brooklyn, Bertha lived a life that impacted everyone she met and moved to California in 1951.

Bertha worked at Rocketdyne before becoming an inspiring educator. She was a Cub Scout Den Mother in the 60s and graduated from CSUN 1969. In...

Myron A. Kusnitz

May 19, 2025

Longtime Los Angeles architect. Beloved husband of Harriet S. Kusnitz, beloved father of Steven Kusnitz and Jill (Peter) Cullen; devoted grandfather of Katie (Colin) Sprague and Jennifer Cullen; adored great-grandfather of Finneas Sprague; also survived by many caring cousins and friends.

Services will be at 2pm Friday at Hillside Memorial Park. In lieu of flowers, memorials requested to Guardians of Los...

Eugene "Don" Haselkorn

May 16, 2025

With broken hearts, we announce the passing of Eugene “Don” Haselkorn on May 16, 2025 at age 93. Born in Brooklyn, NY, “Uncle Donny” (as he liked to be called) was a loving husband, father, grandfather, uncle, brother, son, friend, mentor, pharmacist, business consultant and so much more. He loved life and showered all who knew him with his generosity,...

Stephen James Gilbert

May 10, 2025

Zikhrono Livrakha - May His Memory Be a Blessing

With heavy hearts we announce the passing of Stephen James Gilbert, a beloved husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. While Steve wore many hats: devoted son, younger brother, Marine, UCLA Bruin, native Angeleno, car aficionado, engineer, and businessman, “Papa” was the moniker that gave him the most joy.

He is survived by his wife...

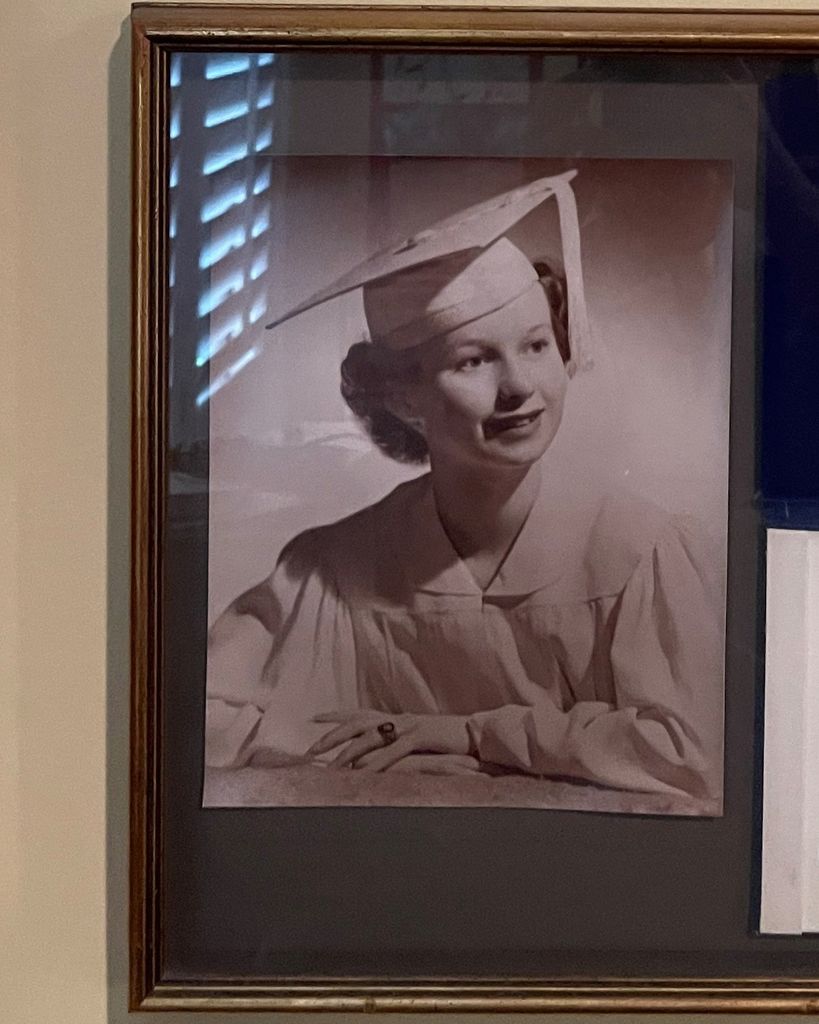

Barbara Ellen Gollin

May 5, 2025

Barbara Ellen Gollin died on May 5th, 2025 at the age of 93 after a short battle with lung cancer. She was born to William and Gladys (Pierce) Dial on December 24th, 1931 and raised alongside her five siblings on a farm in Decatur, Illinois. She spent her early years working as a model and a ticketing agent for American...

Beverly Borine

May 5, 2025

We are deeply saddened to announce the passing of Beverly Borine on May 5th, 2025.

She is survived by, and will be greatly missed by her husband of fifty-three years, Edwin, son, Daniel, daughter-in-law, Stephania, and her beloved grandson, Alexander.

Beverly was a graduate of Temple University, where she received her Bachelor and Master's degrees in Education. She was an educational therapist...

Wilbur "Bud" Petrick

Apr 14, 2025

Bud Petrick: A Life of Service, Leadership, and Community

Bud Petrick, who passed away at the age of 91, was a foundational figure in Pacific Palisades, leaving an indelible mark through his professional achievements and unwavering community involvement.

Early Life and Career

Born in Lincoln Heights, East Los Angeles, Bud spent his formative years in San Gabriel and Monmouth, Oregon. After high school,...

Claire Schweitzer

Apr 11, 2025

It is with profound sadness that we announce the passing of Claire Lillian Schweitzer, who peacefully departed this world on Friday April 11, 2025, at the age of 98.

She was a devoted wife of over 55 years to her beloved husband, Jerry Schweitzer, a loving mother, and a cherished grandmother. Claire touched the lives of many people with her warmth,...

Sol de Picciotto

Apr 9, 2025

Sol de Picciotto

November 26, 1937 - April 9, 2025

Sol de Picciotto, age 87, passed away on April 9, 2025 at his home in Beverlywood, CA. Sol touched the lives of everyone around him with his kindness, humor, and unwavering love, always supporting his loved ones through life's challenges.

After receiving a BS in Physics and a Masters in Electrical Engineering from...

Rochelle (Shelly) Kappe

Mar 29, 2025

Rochelle (Shelly) Kappe

12/30/28-3/29/25

Shelly Kappe, born Rochelle Hope Diamond in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, died peacefully in Santa Monica, CA at the age of 96. Beloved wife of architect Raymond Kappe, mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, she will be missed and remembered by many in Los Angeles, a city that she loved, and by her many friends in the architectural community around the world.

Shelly...

Craig Robert Suchin

Mar 24, 2025

Dr. Craig Robert Suchin passed away on Monday, March 24, 2025 in Encino, California. He was surrounded by his wife Andrea and children Morgan, Samuel, Maxwell, and Bennett. Craig was born in Brooklyn, New York on December 24, 1966 to Maureen (Dervin) and Norman Suchin. He later moved to Merrick, Long Island where he developed his love for science, academia,...

Sign Up To Be Notified of New Obituaries

Email sign-up for new obituary notifications

Please wait

Verifying your email address

Please wait

Unsubscribing your email address

You have been unsubscribed

You will no longer receive messages from our email mailing list.

You have been subscribed

Your email address has successfully been added to our mailing list.

Something went wrong

There was an error verifying your email address. Please try again later, or re-subscribe.

Advance Planning

Contact us today to schedule a consultation and learn more about how we can help you create a meaningful plan that honors your life and provides comfort to your loved ones.